The RemoteFile Protocol

Communication between APX clients and server is actually done using a lower-level protocol called RemoteFile. The world of APX is modelled on top of the RemoteFile protocol before it is sent on the wire. Once the RemoteFile message has been received on the other side of the connection it is immediately modelled back into APX.

This is an introductory text to the RemoteFile Protocol.

Connection End-Points

The key to the RemoteFile protocol is to keep sections of memory in synch with each other over a point-to-point connection. In essence, what we do is to mirror data changes taking place on one side of the connection to the other side. This is done in a bidirectional fashion allowing us to keep data in synch at all times.

In order to describe how this work we will introduce some new terms. First, the two sides of a bidirectional connection is called End-Points. In this text, we will use the terms End-Point A and End-Point B* to differentiate between the two.

Files

In the context of RemoteFile (and consequently APX) we define a file as being a byte-array with some extra properties:

- Name (string).

- Length (unsigned integer).

- StartAddress (unsigned integer).

Additionally, the data in the byte-array must be contigous (no memory holes allowed).

This definition of a file has no relation to files in a file system. For the rest of this text, when we use the word file we mean the definition seen above.

Memory Mapping

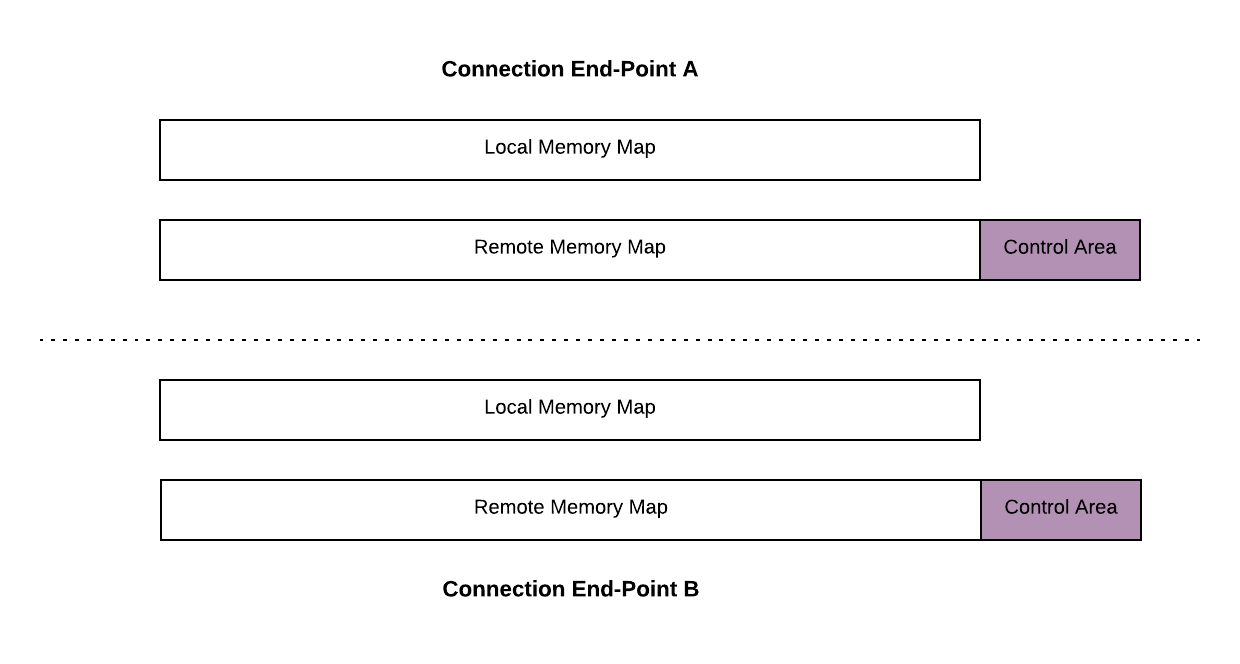

Both connection end-points continously maintain two 1GB memory maps. One is used for locally created files while the other is used for remotely created files. All events that takes place in the local memory map at one end-point is synched to the remote memory map at the other end-point.

The memory maps are obviously virtual memory only. otherwise we couldn’t be using this technique on small embedded devices as was originally intended. Remember that the files created in the map needs to be fully contigous (containing no memory holes), however, it is important to allow memory holes between the files.

This means we only need to back the files themselves by physical memory. In a typical APX session only a few KB is used while leaving the rest of the memory map with empty space.

Writing to the memory map

At any time, each end-point can write data into the remote memory map on the opposite side of the connection. If for example, you want to update a single byte at address 0 you simply issue a write command.

| Write Address | 0 |

| Write Length | 1 |

| Data | 0-255 |

However, you are only allowed to write to addresses where a file actually exists and has been previously opened by the remote side.

RemoteFile Rule Number 1:

Any memory write to an address (lower than 0x3FFFFC00) is illegal, unless:

- A file exists in that address range.

- The file mapped in that range has been previousy opened by remote connection end-point.

The Control Area

The limits (start and end addresses) of the memory maps are as follows:

| Map Type | Start Address | End Address |

|---|---|---|

| Local Map | 0x00000000 | 0x3FFFFBFF |

| Remote Map | 0x00000000 | 0x3FFFFFFF |

The remote memory maps are 1KB larger, This section is called the control area. By writing data to the control area you are issuing commands such as:

- Creating files

- Opening files

RemoteFile Rule Number 2:

Writing to the control area is always allowed as long as:

- The start address of the write is exactly 0x3FFFFC00.

- The length of the write is no longer than 1024 bytes.

Creating and opening files

Files are created in the remote memory by sending a FileInfo structure from one side of the connection to the other.

Contents of FileInfo Structure:

| Name | Type |

|---|---|

| Address | UINT32 |

| Length | UINT32 |

| FileType | UINT16 |

| DigestType | UINT16 |

| DigestData | UINT8[32] |

| Name | Null-terminated string |

For now let’s just focus on the first two as well as the last element of the structure:

- Address

- Length

- Name

Simply put, by sending a FileInfo struct from local to remote side, informs remote side that a file has been created in his memory map. The Address element of the struct is the start address of the file, the Length element is the size of the file and the Name element is the name of the file.

So far we have only informed remote side that a file exists, where it is (the start address), the size of it and its name. This is just informative, nothing actually happens until remote side chooses to open the file. It’s completely up to the remote side to take that descision. For example, if a file is created with a size of 100MB (of virtual memory) but the remote side is hosted by a device with only a few KB of physical memory there is simply no way for that device to open such a large file. For security-reasons, any data write to an unopened file or writes that reaches outside file bounds must always be ignored (or treated as errors).

After the FileInfo has been received and processed by the remote side, the remote side can choose to open the file. It does this by issuing a FileOpen command (written to the Control Area). The only piece of information that needs to be provided is the start address of the file in the remote memory map.

Contents of FileOpen Structure:

| Name | Type |

|---|---|

| Address | UINT32 |

File Synchronization

Once the FileOpen command has been received, the remote side sends the entire file in a single file transfer. This is done by sending a copy of the local file to the remote side. Now comes the important part:

RemoteFile Rule Number 3:

As long as a file of type fixed stays open and there is an update/write of local file data then the same data change must be communicated to the remote copy of the file as a write command.

This is how files stay synchronized on both sides of the connection. We will explain later what fixed files really are.

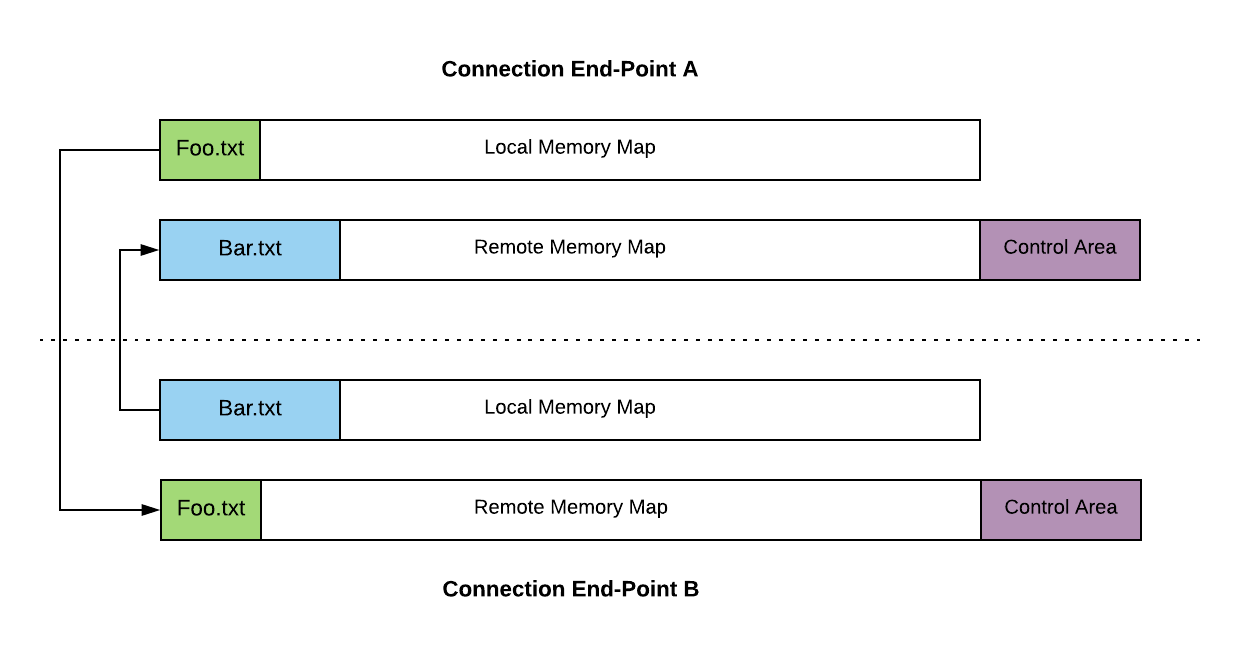

In the example seen below we have two files.

- Foo.txt: owned by end-point A, mirrored to end-point B.

- Bar.txt: owned by end-point B, mirrored to end-point A.